View of the exhibition Ek’ Balam Polifónico, Regional Museum of Anthropology of Mérida

Two interesting temporary exhibitions at the Regional Museum of Anthropology of Mérida (Yucatán) include pre-Columbian artifacts from various periods, photographs, infographics, remnants of Mayan structures, and videos. One focuses on the late 19th century European documentation of ruined Mayan culture through the French photographer Charnay; the other centers on a time of resistance of the Mayan people during the first years after the arrival of the Spaniards in Yucatán in the 16th century.

Under the broad title of “Ek’ Balam Polifónico,” two temporary exhibits offer context and information on the advances discovered on the archaeological site of Ek’ Balam, with each new finding key to further understanding the Mayan world – its anthropology, art and architecture – on the Yucatan peninsula. The latest discoveries made by archaeologists Leticia Vargas and Víctor Castillo shed light on both the recently found pre-Columbian artifacts, and on the interpretation of historical facts.

The name of the site is made up of two words from the Yucatecan Mayan dialect: ek’, which refers to the color black and which also means “star”; and balam, which means “jaguar”. In “Relación de Ek’ Balam,” written in 1579 by the documenter Juan Gutiérrez Picón, the author mentions that the name of the site comes from a revered man named Ek’ Balam or Coch Cal Balam, who founded the city and ruled for 40 years. In the emblem glyph discovered on several stone monuments called “Las Serpientes Hieroglyphics,” Ek’ Balam is mentioned as the name of the site in the Mesoamerican Classic period (200 to 900 AD).

A great explorer

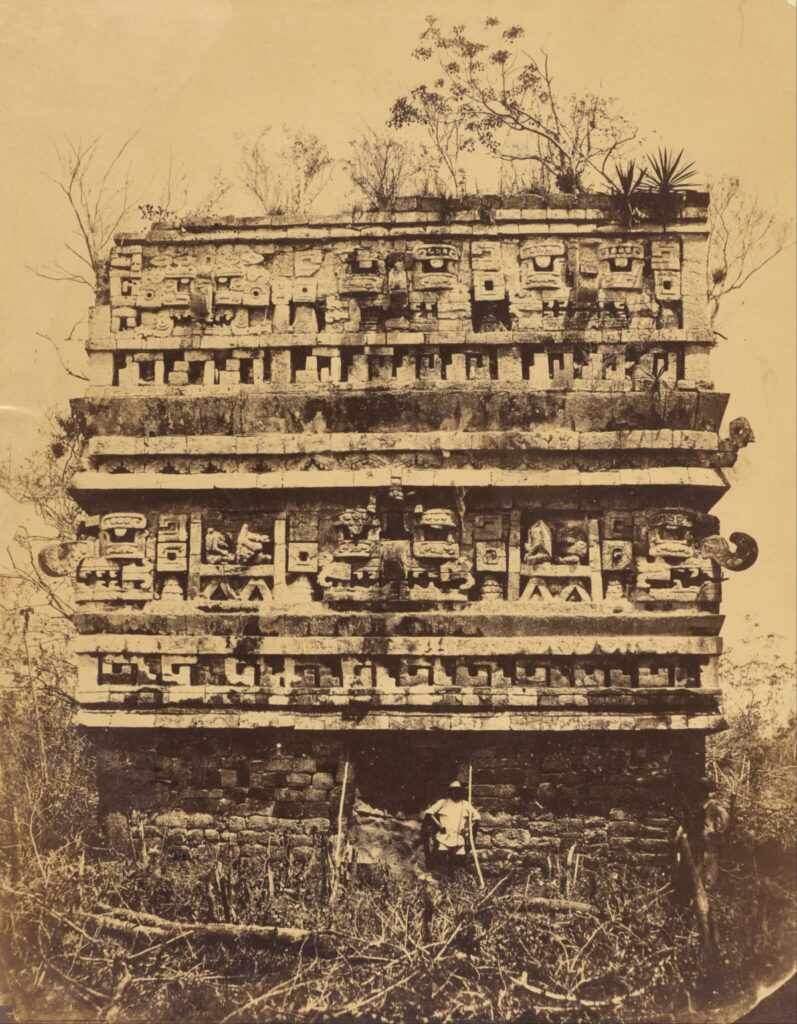

The temporary exhibition “Joseph Désiré Charnay, traveler and explorer of pre-Columbian Mexico,” shares the perspective of a European who achieved worldwide fame for his visits to the archaeological sites of Yucatan, and particularly to Ek’ Balam.

The French explorer Joseph Désiré Charnay visited Yucatán on several occasions, between 1857 and 1886, during his trips through what is today Mexico. During these visits, he used a camera to photograph for the first time ever the archaeological sites he encountered. The novelty, for his time, of the historical, architectural, archaeological and artistic account that he created, is noteworthy. The record he made of places like Izamal, Uxmal and Chichén-Itzá in Yucatán, together with the enormous effort involved in moving camera equipment that weighed 1,800 kilos and the political situation in the country, as well as the lengths he went to to obtain the various materials, improvising solutions for the photographic shots, has made Charnay’s work an enduring and pioneering record for history and archaeology.

The exhibition showcases more than 50 photographs and daguerreotypes of Yucatecan archaeological sites as they were, in a semi-ruined state, at the end of the 19th century, together with new and old findings and interpretations of historical events that occurred in the area of Ek’ balam. Photos such as those of Chichen Itzá or those of the pyramids of Uxmal, together with a replica of the heavy camera used by Charnay, are worth the visit.

Salvaged artifacts

An important set of sculptures, ceremonial objects and remnants of Mayan manuscripts that were burned during the so-called “Auto de fe de Maní” in 1562 form part of the second exhibit “Idols, Persistences/Resistances”.

On the 461st anniversary of the destruction of thousands of sacred objects, artifacts which were later studied and recorded in the quintessential Yucatecan encyclopedia “Yucatán en el tiempo” by various authors (Mérida, 1998), you’ll discover the stories of the indigenous Christians who were accused of being idolaters and tried by the Inquisition. At the time, it was led by the head of the Franciscan province of Yucatán, Bishop Diego de Landa Calderón. The Regional Museum of Anthropology of Mérida, together with the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), has artifacts collected during the excavation work of the Maní site on display, such as ceremonial masks, votive offerings, idols, offerings, all of which are pre-Columbian and point towards the people’s continued worship, both before and after 1562.

Among the pieces that stand out is the incense burner, dated 1250-1530, made of polychrome ceramic; the guardian warriors of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’, with clear Mayan profiles, and the slates with hieroglyphics, together with wood sculptures from the altarpieces of Yucatecan churches and convents, built during the beginning of evangelization in 1520.

The exhibit includes photos and captions that, for teaching purposes and for audiences of all ages, explain what an archaeological site is and the different moments of the discoveries of figures of large idols, along with other small idols for domestic use, and various religious objects.

Thanks to technology, visitors can “relive” in 3D what happened in the Maní Auto de Fe, in the Convent of San Miguel Arcángel in the 16th century, and understand what the indigenous people suffered: 6,300 Mayans were investigated for suspicion of idolatry, 350 were forced to march in the Maní Auto-da-fe procession, 64 were burned in effigy and 84 were forced to wear “sambenitos” to be publicly shamed.

The in effigy punishment, imposed by the Inquisition, was inflicted through a doll the size of a human being that represented the inmate in question. It was carried out on those who had died before finishing the interrogation process, those who had escaped and those who simply never were captured.

A new sense of criticism

“The exhibition is important, because it offers a new critical and analytical lens to understand the result of scientific research of historical documents and the material evidence that was found in the foundations of the buildings,” explains Arturo Chab Cárdenas, director of the INAH Center in Yucatán. In the exhibit, researchers from INAH, the Autonomous University of Yucatán, the Archdiocese and other scientific and academic institutions – such as Dr. John Chuchiak (Missouri State University), who has participated in much of the exhibit’s curation– , contribute to a new assessment of the historic event led by Bishop Diego de Landa.

The remnants of the archaeological places and objects and historical documents found indicate that more than 100,000 stone, wood and clay images were destroyed in the huge bonfire of the Maní Auto-da-fe; 27 Mayan codices (or folding books); 13 stone slabs used as altars; 22 carved stones, and 197 vessels for offerings.

“In this exhibition we can see the remnants of the bonfire, and although the past cannot be recovered, trying to preserve its memory is possible and to learn from mistakes of the past for building a better tomorrow,” says the director of the Regional Archaeological Museum, Bernardo Sarvide Primo.

This exhibition is evocative of St. John Paul II’s words in Izamal, in a famous gathering with indigenous communities in 1993: “From the beginnings of evangelization, the Catholic Church, faithful to the Spirit of Christ, has been a tireless defender of the Indians, protector of the values that existed in their cultures, promoter of their humanity against the abuses of colonizers, sometimes without scruples, who didn’t know how to see in the indigenous people brothers and children of the same Father God. The condemnation of the injustices and outrages committed by Bartolomé de Las Casas, Antonio de Montesinos, Vasco de Quiroga, José de Anchieta, Manuel de Nóbrega, Pedro de Córdoba, Bartolomé de Olmedo, Juan del Valle and many others was an outcry that led to legislation inspired by the recognition of the sacred value of every person and, at the same time, a prophetic testimony against the abuses committed during the times of colonization”.

Two interesting exhibits, which should be visited after previously reading up on, to learn about these historic events, and to shed light on the truth, which does not fold in the face of sectarianism.

Translated from Spanish by Lucia K. Maher