To measure how Catholic schools around the world are doing, you could use any number of indicators. You could, for example, look into qualitative aspects: the educational level of the centers or the extent to which they’re fulfilling the religious and anthropological missions that guide them. But it’s easier to analyze a quantitative yet telling aspect: enrollment trends. A recent report does just this, and the findings are more positive than negative.

Around the world, just over 60 million children study in Catholic schools, approximately 5% of all students. A report published by Global Catholic Education –a non-profit based in the United States– sheds light on the regions where the schools are experiencing growth and where the opposite is happening, what their “market share” is compared to other profiles of schools, which grade levels have the highest enrollment, and the socioeconomic profile of Catholic school students. In addition, the data shows the extent to which state funding influences all of these factors.

Continued, albeit uneven, growth

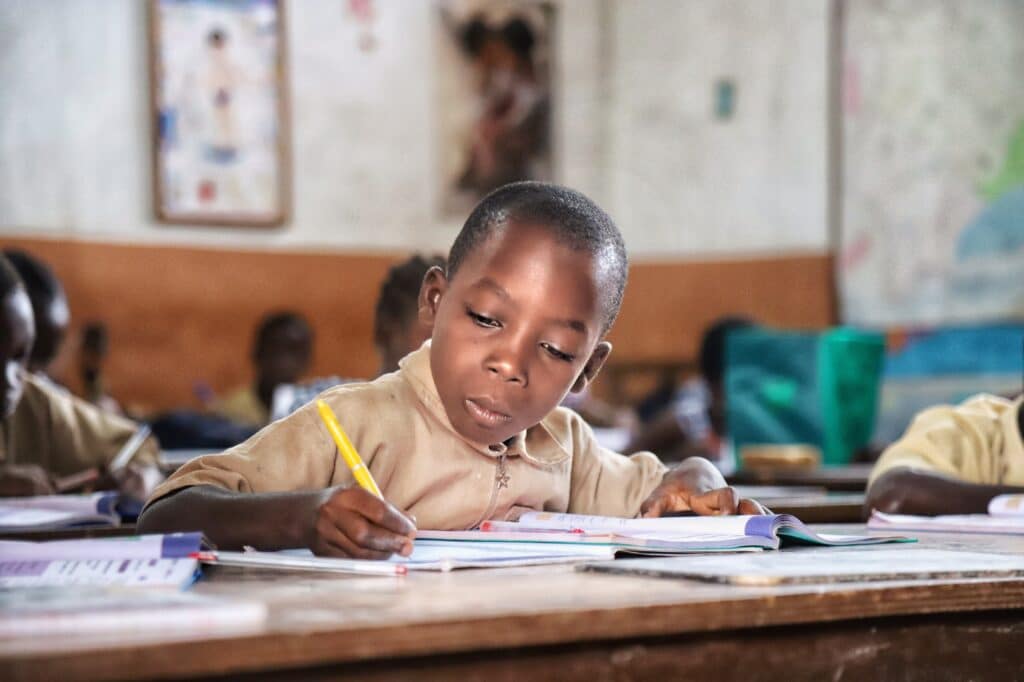

It may come as a surprise that when it comes to countries with the most students in Catholic schools, Europe or America aren’t at the top of the list. India ranks first, followed by four sub-Saharan African nations: Congo, Uganda, Kenya and Malawi. On the one hand, this can be explained by demographic reasons –total population, birth rate–, but the strength of Catholic teaching in these regions also plays a role.

Four in 10 students enrolled in Catholic school are in Africa, and less than a sixth are in Europe. The difference is even greater when it comes to primary school.

A simple look at the evolution of enrollment numbers in Catholic schools will do. Worldwide, they’ve doubled overall since 1980. But while they’ve doubled in Asia and Oceania, and quadrupled in Africa. They’ve hardly changed in Europe and the Americas. The overall growth has been continuous, although it intensified in the first decade of the century, and has since slowed. Since 2018 there’s been a slight decline, which is almost entirely due to the decline in enrollments in the Americas. It’s likely that school closures due to COVID – which were especially long in some Latin American countries and in many states across the U.S. – are behind the change in trend, though it’s still too soon to tell.

Currently, of all the students enrolled in a Catholic school, four out of 10 are in Africa (that percentage exceeds 50% when it comes to just primary school students). In 1980, that figure barely reached two out of ten. The opposite has happened in Europe and America: two thirds of all the Catholic school students worldwide were once on the two continents; now, they only represent a third of the total. As can be seen, similar to the trends in the number of believers or religious vocations, the West is no longer the educational engine of the Catholic Church.

At the service of the poor

Despite the overall growth of students in Catholic schools, the percentage that it represents over the total child population has not varied much in the last four decades: worldwide, it is 5% in primary education, and somewhat less in secondary education. However, differences by region can also be observed here, both in the current figures and in their evolution. The continent with the highest proportion of students in Catholic schools is Oceania, where one in five attend a Catholic institution. This is due to the number of Catholic schools in Australia, and the fact that they are mostly funded with public money. Africa is also above average, double, to be precise. On both continents the percentage has increased since 1980, unlike in the United States.

When a family chooses Catholic school, in addition to geographical differences, there is a clear economic factor in the mix: these centers are especially in demand among the most vulnerable families within each country. This is especially the case when it comes to primary school: 70% of students come from low or lower-middle income families; the percentage drops to 60% in secondary school.

The effects of state funding

Logically, whether or not state funding is available greatly influences the socioeconomic profile of students. Many Catholic schools in Africa count on public funds (as is the case of Congo, Uganda, Kenya and Malawi, for example).The same thing happens in Australia and, within Europe, in Ireland, Belgium and Spain, which explains the high demand for these centers and the different socioeconomic profiles of their students. On the other hand, in India (the country with the most students enrolled in Catholic schools) and the United States, public funds can’t go towards religiously affiliated schools.

Lack of funding to build new centers limits the growth of Catholic education systems around the world

Even where the State subsidizes tuition, the construction of a new center is usually borne by the school itself, which has to seek private financing. Throughout poor countries in African where many schools had to close their doors after the pandemic (since a large proportion of their students never returned), opening new schools is proving very difficult.

On the other hand, as is becoming more and more frequent in the poorest regions of the world, Catholic schools are encountering increasing competition: low-cost charter schools (i.e., private schools which receive state funding), a phenomenon widespread in parts of Africa and Asia. These schools tend to offer more personalized attention with higher academic standards, which were two reasons that once led many parents to opt for Catholic education over public education.

Another challenge for Catholic schools in these countries is increasing their student body population in secondary school. While their numbers are high when it comes to pre-school and primary school, (which one would assume would guarantee a robust student body in secondary school), the truth is that many students do not continue beyond that. In Africa, only four out of 10 students finish secondary school. The phenomenon is largely due to the financial needs of many families, and it affects every profile of school, although it would be interesting to see – the study does not address this– whether the dropout rate is lower within Catholic school systems.

Latin America and the United States, two very different realities

The report groups North, Central and South America as a single region, and their data is pooled. However, the reality of Catholic school systems today and their evolution in recent decades is quite different between Latin America and the United States. While enrollment continues to increase in Latin America, albeit at a slower rate than in previous decades, in the United States it has fallen sharply since 1980. As previously noted, the lack of public funding is a major obstacle, and that’s on top of the added competition from charter schools, which do receive funding and which –as occurs in Africa with low-cost private centers– offer a teaching model based on similar values.

During the 1960s, there were more than five million students in Catholic schools in the United States. Today that number barely reaches 1.5 million. Except for a brief period of growth between the late 1990s and early 2000s, the decline has been continuous, becoming more acute in recent years. In addition, it especially affects the earliest educational stages: preschool and primary school, which directly affects secondary school enrollment in Catholic schools.

Even before the pandemic, many Catholic schools were closing, and COVID finished off others who were surviving by a thread. However, the latest data points to a rebound in the past academic year: enrollment numbers increased and there are more families than ever on waiting lists. This points towards a possible trend in the not-so-far-off future, and that is that if funding is found to build new schools, student enrollment could swell, although it’s still too early to tell.

Translated from Spanish by Lucia K. Maher