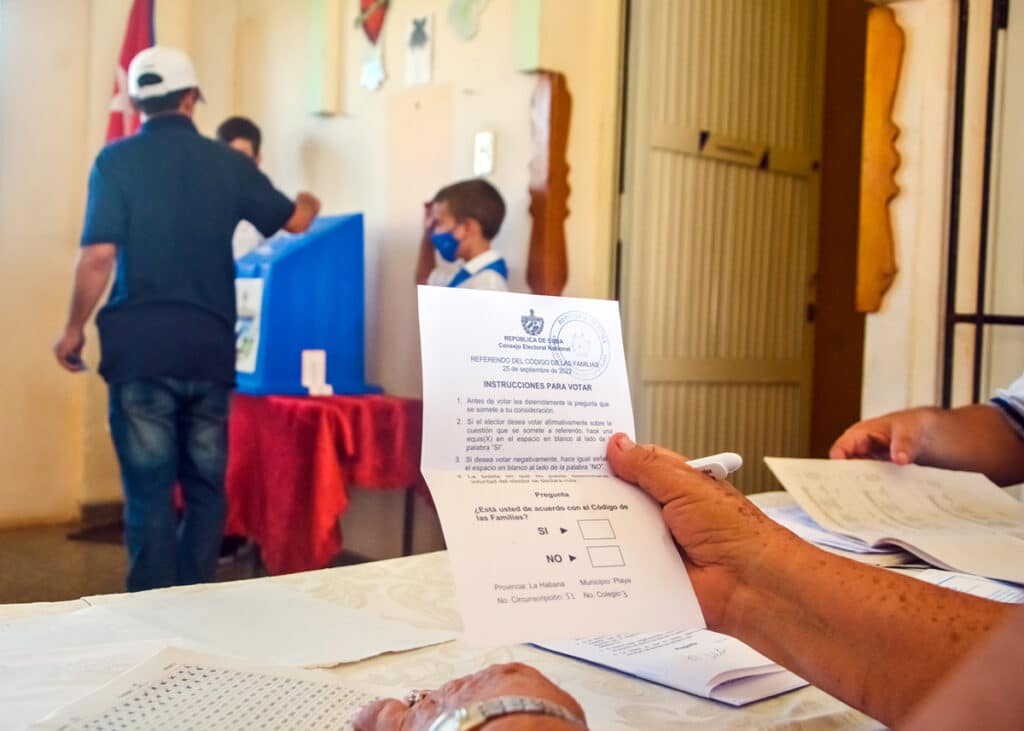

A member of a polling station staff in Havana shows the referendum ballot (photo: Juan Moreno)

Similar to representative democracies, “single-party democracies” – as a high-ranking European official described the prevailing political system in Cuba – also hold referendums. Only, unlike the uncertainty that overwhelms governments of the former type when they consult an issue with the public, in the latter, everything is more predictable: the government option will always triumph.

It’s just happened. The Cuban government put the new Family Code (FC) to vote, and the first results show that 74% of the electorate visited the polls (a fairly low percentage compared to the usual turnout), and that a little less than four million voters approved it, compared to the almost two million who voted against it, a truly striking figure (in the 2019 constitutional referendum, there were only 706,000 votes for the option “NO”).

Fraud? It’s not too common there, although some voters complained of irregularities. Feeling personally committed to the actual content of the standard up for vote? No. “I’m going to vote ‘yes’ because, ultimately, nothing is going to change,” was one of the most recurring responses in the days leading up to the vote, when voters were asked which way they were leading in an informal setting.

To the outside observer, the obvious question is: if nothing is going to change, why vote? And the explanation is that the authorities knock on your door early on to remind you that it is “your duty” not to take too long to make it to the polling station. Now, once in the voting booth, why vote ‘yes,’ if the ballots are anonymous and there are no video cameras? Out of fear of “complicating” things. People are often inhibited by well-founded or imaginary fears.

But from within the government, this is far from the way things are seen: the people voted for the Family Code because it is “a monumental work, fruit of the amount of knowledge and experience that conceived it, and because of its brilliant singularity: it turned love into Law” (hence the capital “L”.)

Marriage redefined

Among the “battles” with which the country believes to be positioning itself at the forefront of individual rights is the redefinition of marriage, which in the final version of the code was left as “the voluntarily arranged union of two people legally authorized to do so, with the aim of sharing their lives, on the basis of affection (from this word, affections, the pro Family Code campaign certainly received important fuel), mutual love and respect” (art. 201).

The new definition of marriage thus opens the door to same-sex marriage –with the right to adopt children–, a personal win for Mariela Castro, daughter of former President Raúl Castro and niece of Fidel Castro, the “historic leader” of the revolutionary process, who curiously, decades before, encouraged the population to reprove young men who exhibited “feminine” and “Elvispresleyan” behaviors.

There are doubts about the consequences that the legal consideration of “progressive autonomy” and “in the best interest” of the minor may have for the authority of the parents.

For Mariela, director of the National Center for Sex Education, the government’s former denigration is a trivial offense, that nobody in the highest political echelons was responsible for: “No one can be blamed, no generation, because all the victories on the roads to ensuring rights are full of contradictions and difficulties. (…) Socialism isn’t made overnight”.

Now, in addition to same-sex marriage, “multiparenting” is allowed: the possibility of recognizing a person “beyond the two ties of filiation” (art. 55) as such, namely, two fathers and one mother, two mothers and three fathers, etc., since the parental bond can be designated “regardless of the biological link or any genetic component”.

Closely related, we’ll find surrogate motherhood, here under the qualifier of “solidarity” -without remuneration, based on “the right of every person to have a family” and available to those who cannot exercise said prerogative “for a reason that makes pregnancy impossible”, as well as for “single men or male couples” (art. 130). Under the new law, parenthood is recognized to the couple which requested help to have a child in this way, as well as to the woman who, despite not having contributed gametes, carried the child in her womb.

Lastly, in the FC we’ll find issues related to parental responsibility, progressive autonomy and the best interests of minors (replacing what was formerly included as “parental authority”). One of the duties within the aforementioned parental “responsibility” with respect to children and adolescents is “to accompany them, in accordance with their progressive autonomy, in the construction of their own identity” (art. 138). The question that many have been raising is whether, in the event that the child claims their sex assignment to be erroneous, the parents will have an alternative option to “accompanying” them in a transition process. If the court decides that the child is mature enough and that it is in their “best interest” not to be contradicted, where will the parents’ authority be to redirect the situation?

With subtlety and kindness…

The Code has finally gone into effect. But long before, the pressure for it to pass had been strong, and the media was entirely supportive of the campaign.

The government felt it had to do things this way. It feared that, as happened in the prior debate surrounding the 2019 Constitution, ordinary people, opposed to the reformulation of marriage, would simply vote “no”. And that, given the degree of the population’s own weariness stemming from the serious hardships of daily life –blackouts, food shortages, the transportation crisis, etc.–, they would cast their votes to “punish” anything related to the text’s contents.

That’s why the government sought, on the one hand, to subtly influence the population, with television spots of the elderly, children and smiling couples in a sea of hugs and affectionate gestures, and via televised “debates” between experts, who, as it turns out, were all likeminded. Soap operas proved another channel of influence. Cubans, insofar as soap operas are concerned, have been receiving strong doses of the new family doctrine via the families and characters portrayed.

In the last production of the summer, Tan lejos y tan cerca, what they call “alternative models” of family also made appearances, with a lesbian relationship and another couple interested in exploring “polyamory”. “The naturalness with which [these relationships] was presented was very well done, particularly plausible in times of intense debates before a referendum for a new Family Code,” a pro-government reporter noted.

… But showing their teeth

There have been, however, more radical messages, directed against the “haters,” or anyone not in favor of the new code. One of its most active defenders, the homosexual activist Paquito el de Cuba, posted about the Cuban system’s belligerent ways on his social media.

“There will be – he warned – traps and deceit from now until September 25, from authorities and individuals who are always committed to creating problems for us and leading us towards division, hatred and grudges, either for their own benefit or as conscious hostages or unaware of a hostile and abusive policy, which does not care one iota about the well-being of our families. We already know these tricks too well, and we know how to shut them down.”

The government has equated any attitudes contrary to the Code as attempts to go “against the Revolution”

Previously, in another post, he warned against any attempt to debate with those who had legitimate doubts about the new law, or to give them space in the media to raise their doubts: “Are you stupid or naive? No playing around at bourgeois democracy when it comes to the Family Code”, he affirmed.

The site Razones de Cuba came out using the same undermining tone. Those against the new law were, according to the online paper, “the worst, those who only see things with hypercritical eyes. They look for any opportunity, the slightest pretext, to use it against anything that resembles Revolution or Socialism.” There was no margin, as it were, for any discrepancy: “The haters’ excuses are no more. The will of the people, as always, will be law.

Except that the “will of the people” was not originally the one that was destined to prevail. One afternoon in the late 2000s, the Cardinal of Havana, Jaime Ortega, told this very writer that the then President Raúl Castro had given him a personal guarantee: “Don’t worry: as long as I am president, there will be no gay marriage in Cuba.”

Well, it is no longer Raul Castro’s country (at least not nominally). Perhaps that’s why he raised his hand in approval of the Code when Parliament unanimously voted on the final wording on July 22.

Now that “the people” have spoken, the government can only boast of having a “modern” Code, thanks to the exercise of democratic voting, the same exercise, curiously, that many Cubans would like to have more of a say in when it comes to deciding on issues that affect them much more, like the impossibility of electing a political option other than the Communist Party.

Translated from Spanish by Lucia K. Maher