Inner courtyard of Casa Batlló (Barcelona), covered with glazed ceramic tiles (Photo: Casa Batlló)

The work of Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) is internationally known. The Japanese – for example – are fascinated by the originality and beauty of the Basilica of the Sagrada Família, perhaps his best known and most visited masterpieces, despite being unfinished. Most of his works have been studied and interpreted and, of course, photographed countless times; but Madrid has not hosted an exhibition like the Centro Centro’s for more than 20 years. The Gaudí exhibit is proving to be a success and has been extended 20 more days. What do Gaudí’s works have that attract thousands of visitors from all over the world? What is it about his architecture and personality that countless find so attractive?

The curator of this exhibition Charo Sanjuán’s effort to bring together architectural plans and models, drawings, furniture, architectural elements, ceramics and even historical photos, is splendidly reflected in the exhibition, which focuses above all on the buildings that are part of UNESCO’s World Heritage Center: Parc Güell, Palau Güell and Casa Milà –”La Pedrera”–, Casa Batlló, Colonia Güell’s crypt, Casa Vicens and the Sagrada Familia’s crypt and Nativity façade.

Some of sketches and drawings on display are originals for these very works, and the models (which are some of the most impressive out there) strikingly reflect the actual masterpieces built thereafter. Without a doubt, the exhibition helps spark interest in traveling and seeing Gaudí’s large-scale work in person. The exhibit’s explanatory texts and seven-part design, which takes visitors through its different rooms, shed light and understanding on his architectural work.

The book of Nature

This presentation of Gaudí’s works reveals the originality and symbolism of his forms, the cheerful naturalistic ornamentation of his buildings, and the variety of textures and colors of the materials he used. But above all, his inspiration in Nature stands out, already clearly visible in his artistic work with its incorporation of timeless traditions, the unique and the universal. Some of the details only caught by the extra attentive eye seem to be taken directly from the great book of Nature. “The architect of the future will be based on the imitation of nature, because it is the most rational, durable and economical of all methods,” Gaudí once said.

As a young man, Gaudí suffered from rheumatism and was bedridden; maybe that’s what helped develop his astounding capacity for observation. His love for nature — the birds, the mountains, vineyards — began to nourish his imagination and was later manifest in the organic forms of his buildings. In them, you’ll find everything from the stalactites of caves to the sea snails or shells of the ocean. The curved and scaley roof of the seemingly enchanted Casa Batlló’s resembles both the back of a scaly-skinned lizard and a sea creature.

The curved façades of “La Pedrera” and Sagrada Familia also simulate waves and the shape of a forest. “The interior of the temple – said Gaudí– will be like a forest. The pillars in the central nave represent palm trees, symbols of glory, sacrifice and martyrdom, whilst those in the lateral naves are laurels, symbols of victory and intelligence.” The temple of the Sagrada Familia was the great project of his life. Gaudí was a believer and he poured all his talent into this masterpiece. He was deeply involved in its construction, putting his body and soul into it for years. He collected donations so that the construction of the temple would not be interrupted, but at the same time he was aware that the work would last many years, prompting him to once say: “Everything that usually lasts through time suffers interruptions.” Montserrat Rius, who worked at his house in Parc Güell, described him as a “very simple and calm” man, adding “he was happy if someone helped him, but only for what was necessary”.

Going back to the origin of things

For Gaudí, “originality consists in the return to the origin; thus, originality is that which returns to the simplicity of the first solutions.” But beneath the original shapes and forms of his works, his building genius stands out too, from his innovative solutions, such as the catenary arches used in Colegio de las Teresianas (one of his first projects) to the funicular arches he incorporated later in his career. In all these constructive or structural systems, rationality prevails: the columns, arches or vaults fulfill their structural function; they are not mere decoration.

Gaudí’s mastery in his use of materials is also admirable. He managed to create poetry with stone, symphonies of color with glazed ceramics, and mosaics using the trencadís broken ceramic technique. And no less admirable are his wrought iron designs, like the ones he made for “La Pedrera,” an authentic masterpiece of inventiveness and plasticity, achieved without a doubt thanks to his skills from his time learning his family’s boilermaking trade.

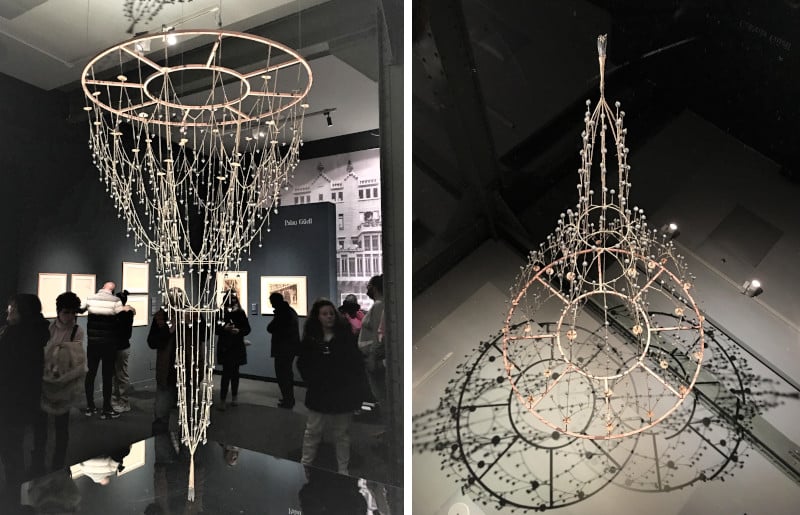

One of the most interesting experiences of this exhibition consists of understanding the spatial structural system invented by Gaudí. In the central room of the exhibit, a polyfunicular model is suspended from the ceiling, made with ropes, weights and steel, which allows you to get an idea of the system that Gaudí used (which hinges on funicular curves) to build vaults such as the one in the Crypt of Colonia Güell or that of the Sagrada Familia. The final effect of the exhibit’s model is achieved by looking at a mirror on the floor, which reflects how the vault formed by these arches would look.

Gaudí’s unique work method, visualizing the final product before embarking on its construction, turned his workshop into a laboratory for experimentation with organic forms. His great imagination and virtuosity were allied with careful study and meticulous work to design every detail. He had a holistic concept for each project, bringing the decoration, furniture, and other aspects together to form the whole. Gaudí describes the architect as “the synthetic man who sees things clearly as a whole before they are done, who situates and connects the elements in their plastic relationship and at the right distance.” In the exhibition you can also see some of the furniture designed by the Catalan artist: an ergonomic wooden chair from Casa Calvet, and various handles and door knobs from Casa Milà.

A free spirit

The rich artistic heritage of the Catalan architect reveals his free spirit, his eagerness to find a greater freedom that transcends that which is merely material. Gaudí’s creative work was an extension of his personal life. Regardless of critical opinions, he would highlight certain ideas from history and, in a subtle way, make them his own with his unique style. But, above all, he explored uncharted waters within the field of architecture of the time and moved freely within its limits, exploring and experimenting with non-orthogonal and rectilinear spaces. These breakthroughs are now common currency, as seen in the architecture of Frank Gehry, or before Gehry in Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel. Gaudí sought balance, and understood clearly how to achieve it: “For harmony – that is to say equilibrium – contrast is necessary: light and shade, continuity and discontinuity, convexity and concavity…”. The exhibition offers visitors the opportunity to compare Gaudí’s Vicens (1888), Calvet (1898), Batlló (1904-12) and Milá (1906-12) houses, including their design plans and models, showing the Catalan artist’s evolution towards a more organic architecture, tending towards curves and more daring shapes.

The historical context surrounding Gaudí’s work is not only interesting but revealing: the cubism of Picasso and Braque (1907-17); the Russian revolution of 1917; and, more influential in his work, the prominent group of artists who developed Catalan modernism (1885-1920). Dalí thought that Gaudí had been a precursor of surrealism (the former appears in a video in the exhibition). But perhaps the common denominator with this cultural movement was his desire to transform society, to seek greater freedom, albeit through different means. Gaudí did just this through his own life, and that’s perhaps why he said: “In order to do things right you need: first, love, second, the technique.”

Translated from Spanish by Lucia K. Maher