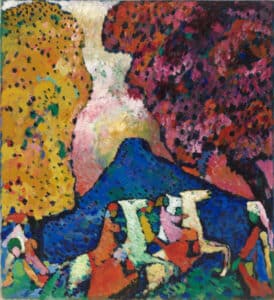

Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle / Photo by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Within the ascending spiral ramp that forms an impressive central void of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, a symphony of chromatic sounds has resounded for several months now. The pictorial language of Vasily Kandinsky has expanded through its rooms with an exhibition that brings together almost one hundred works by the artist and that are on view until September 5.

The building on Fifth Avenue – designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and open since 1959 – still stands the test of time. And finding another space that matches its perfection for showcasing Kandinsky’s works would be a difficult task. His paintings, which were once avant-garde, still move us and help us understand our world.

Who was Kandinsky?

Kandinsky harbored a world full of fantasy within. A world of enchanted adventures and medieval legends that came from the Russian and German tales that his aunt told him as a child. His love for Moscow, where he was born in 1866, and his passion for music forged in him a free and lyrical spirit. His exquisite sensitivity, cultivated on his escapades through farm villages throughout Russia, gave him an extraordinary mastery of colors and shapes. When he contemplated these popular scenes, he would memorize the chromatic impressions: they were for him like strokes of color that left him engrossed.

Hence, his paintings have a deep chromatic beauty. He wanted to “attract the viewer through great force”; let them wander in amazement at the various emotions expressed on the canvas, even though he always deliberately concealed their deeper content. Kandinsky was not only synesthetic, and linked colors to musical sounds, but he also associated different states of mind with colors. He was convinced –and he told his composer friend Schoenberg– that painting could “develop the same energy as music” and could take into account the psychological influence of colors on the viewer: “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”

His desire to delve into art led him to drop out of law school and move to Munich. It was there, during that first stay in Germany (1896-1917), and already working full-time as an artist, that, in 1910, Kandinsky gave birth to what would become known as abstract art. A discovery that would gradually and progressively distance his work from real, concrete objects, and that would revolutionize the world of art. The independence and exuberance of color in his paintings, with increasingly blurred landscapes, figures and houses, created imprecise impressions of colors and shapes.

Despite all this, over time, his painting became more geometric, with isolated elements and cooler colors. Undoubtedly due to the technical-functional influence of Bauhaus Academy on him, but also in part from what was avant-garde in Russia at the time, although his originality and expressive nature caused him to distance himself from it. His written works had significant influence, especially his first book, but the second one too: “Point and Line to Plane,” which was published in 1926. Both served to reinforce his ideas. His theory influenced many other artists, such as Kupka, Malevitch and Mondrian, who molded their own styles from similar concepts.

For Kandinsky, the circle was the perfect shape: an absolutely cosmic symbol! And ultimately, a romantic element full of inner strength that, along with angles, curves and straight lines, that would form part of his geometric vocabulary, at a time when his work became more intellectual and less dramatic.

However, the New York exhibition begins with paintings from his last stay in Paris (1933-1944), and continues up the Guggenheim ramp in reverse chronological order. The paintings, which came to life in the French capital after Kandinsky moved there following the closure of Bauhaus Academy, reflect the influence of the natural sciences and the surrealist movement. Some of them seem like they’re taken from a microscopic or biomorphic world and resonate extraordinarily with Miró’s work. They possess an impressive formal richness, displayed on their canvases like a universe of floating elements: seahorses, amoebas, serpents…, but also checkerboards, bands, stairs, harps, mills…, and circles, lots of circles.

What can we learn from Kandinsky?

To contemplate Kandinsky’s paintings is to rediscover his genius strokes of artistic creation. And, quite possibly, to enlighten our very lives, which are sometimes, more or less, lacking in creativity. When Kandinsky stated: “I feel the harmony of colors and forms that come from this world of joy,” he was at the same time very clear that simple chromatic harmony was not the ultimate goal of his painting. He aspired to express the force and drama of life, with its contrasts and contradictions. And that is why he was looking for harmony that was full of substance, the result of great dimensional and formal diversity, with independent pictorial elements of different tones and intensities. But without ever forgetting the psychological meanings that accompany colors and offer their deepest meaning.

As a good man of the East, he used analogies and associations to increase the symbolic richness of his artistic vocabulary. If anything can be learned from Kandinsky’s art, it is the importance of expressing emotions, which he achieves through shapes and color. But not empty emotions, rather, those that make the soul vibrate. The different sounds of his brushstrokes encourage us to leave the monotonous gray, which would be something similar to expressing ourselves without changing the tone of our voice, without stressing what is most important. His brushstrokes also encourage us to reinvent shapes, because they wear out over time. In short, to make a symphony from existence itself, as he does with his paintings, in which violins, trumpets, cymbals and double basses sound.

However, looking at his pictorial artwork as a whole, his ability to establish completely new premises which later transformed the world of art remain his greatest talent. Kandinsky, influenced by the idealists, seeks to renew painting, salvage the hidden essence behind empty formalisms and mere external appearances. And it is within this process of birthing new art that another, twofold one, takes place: a spiritual and vibrant one, with the potential to shape us into the future and with the capacity to renew the existing materialistic and utopian society. In doing so, he comes across a new language: that of the abstract and colorful. He knew he would be sailing against the tide, because the Russian avant-garde at the time had very little appreciation for that which is romantic and transcendent. But he was aware that art, like life, must evolve or it ends up dying. To that end, he succeeded in turning abstraction into the most perfect way to breathe life into the society of his time, despite the fact that the most dominant and persistent motivation behind all his work would continue to be spiritual expression.

The Guggenheim exhibition “Around the Circle” captures the very core of Kandinsky’s work: a circular path in search of that ideal. An ideal that he tries to include in all his paintings in the form of magical freshness and spontaneity. His paintings seem to reveal universes filled with ideas, seas of intense contrasts with floating and vaporous tones… There is no sense of repetition. Everything seems to be the result of momentary impulses. And yet, it is the result of the meticulous study of details, of prior, hard work. As with so many great artists, there is much to learn from his work.

Antonio Puerta López-Cózar

Architect

Translated from Spanish by Lucia K. Maher