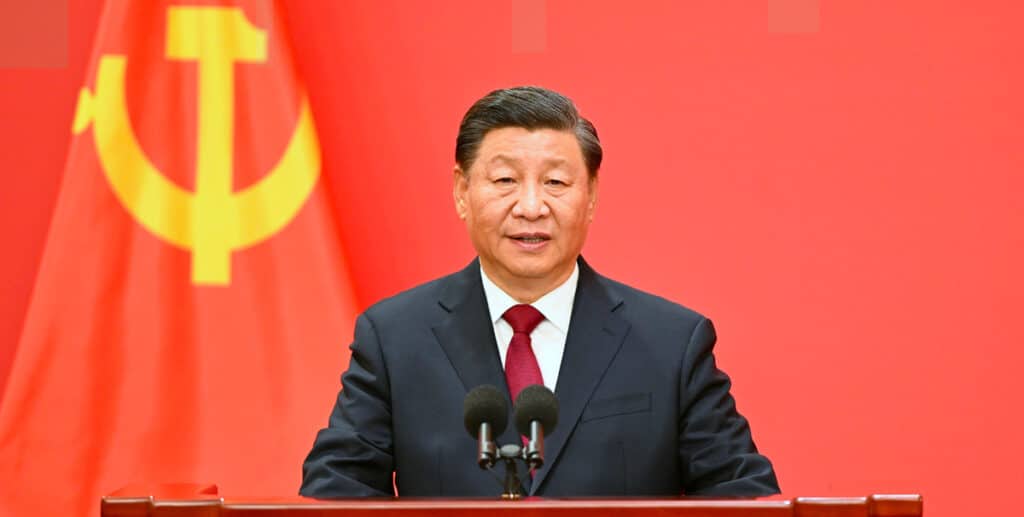

Xi Jinping addresses the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress (CC: CPC)

The National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), held between October 16 and 23, is an event that takes place every five years to appoint or confirm its leaders. This year, the country’s president was not re-elected after ten years in power. The appointment of Xi Jinping as leader with an indefinite term ratifies a change of era: the pragmatism inaugurated by Deng Xiaoping has come to an end and centralization and ideological pursuits have begun.

The Congress was held at a time of turbulence. China’s economic situation, which has seen a decline in its growth, and consequent social repercussions, coincides with the complex international scenario brought on by the war in Ukraine, which tests the role that the communist regime wants to play on the world stage. These realities, in combination with the internal situation of the country marked by the drastic covid zero measures, required a greater presence of the regime to shape the public opinion of China and abroad as a strong and cohesive power, capable of carrying out the “Chinese dream” referenced by President Xi Jinping at the 2017 Congress.

Since then, the regime has promoted the symbolism of certain dates, and all of them converge in 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the year in which China should have risen to the rank of first political and economic power. Gone is the slogan of a “peaceful rise,” which was omnipresent during the previous president Hu Jintao’s term. These ambitious aspirations mark a change of era that revokes the regulated succession in the leadership of the CCP every ten years, as Deng Xiaoping, the father of post-Maoist China, set in 1982. In contrast, Xi Jinping intends to move in the wake of Mao, to the point that Xi Jinping’s thinking was equated with that of Marx, Lenin and Mao in the previous Congress, although more so for his methods than the actual content.

In the last ten years, Xi has been forging the image of an indispensable leader, who must continue to lead at the helm of the State and the Party to carry out what he calls “the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. From the moment that an amendment to the Constitution abolished the limits of presidential terms in 2018, the path towards his continuity in the general secretariat of the CCP became unobstructed. However, he has yet to take the step that would equate him with Mao: that is, becoming Party Chairman. This would have automatically led to the devaluation of the position of general secretary, a synthesis of all the powers in China. Deng Xiaoping abolished the position of president in 1980, and advocated an orderly succession to avoid the internal clashes of the last years of Maoism. Xi might not have taken it this far because he would not have considered it necessary; there is no doubt who is in charge.

Xi maintains a tight grip

As for other aspects, Xi has long since upended the unfounded expectations that he could loosen the pressure exerted by the regime on its citizens. Xi Zhongxun’s son, a colleague of Mao’s from very early on, suffered, along with his family, the humiliations of the cultural revolution. Official historiography has always made a point of noting this, but the conclusion, both in Xi Jinping’s life and in Chinese politics, has not been to advocate for liberalization but rather to strengthen the communist regime, the only guarantee to maintain the country’s stability.

Stability is the permanent obsession among China´s rulers, never losing sight of the country´s historical cycles of unity and disintegration throughout its imperial age. Stability, which passes through the absolute rule of the Party, is a good for which all other interests must be sacrificed, including personal and family interests. This is what Xi Zhongxun believed, and his son shares this conviction. From there, he infers that China’s problems do not stem from authoritarianism but from the way in which that authoritarianism is exercised.

The times of Deng, with their “being rich is glorious” slogan, have passed, and Xi underscores that economic development cannot question the established order

Some images of the closing session of the Congress speak for themselves. Former President Hu Jintao, 79, was forced by Xi to leave, despite his explicit objection. Official sources have attributed Hu’s dramatic departure from the meeting to health problems, although in reality it could be interpreted as a dramatization about who holds the reins of power. It was a way of ending the era of previous secretaries general, including Deng Xiaoping, by a leader like Xi who lost neither his composure nor his parsimony during the incident. Perhaps it was also a way of expressing that during Hu’s mandate, the CCP had been weakened, also in its ideological convictions, and had been affected by corruption and an inefficient bureaucratic system. These were the words used by Xi to describe that period in his address: “Cult of money, hedonism, egocentrism and historical nihilism.”

Ideological purity to counter corruption

The “purge” of Hu Jintao expresses the triumph of a more ideological party, alien, in theory, to pragmatism and represented by “a socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Hence Xi Jinping’s reiteration during his speech that social policies, particularly in health, education or the environment, will be strengthened, conveys the idea of a return to an “ideological purity” continually threatened by government or private corruption. In this sense, in this very speech several self-criticisms surfaced with references to economic inequalities between rural and urban areas, deficiencies in scientific and technological innovations, food security and supply chain failures.

However, the conclusions Xi draws from these situations are influenced by ideology, making historical materialism the only interpretive code of reality. A position very far from that of “Seek the truth in the facts,” Mao’s slogan updated by the pragmatism of Deng Xiaoping. Marxist determinism makes the resolve of a political leader to overcome all kinds of obstacles matter more, even if he must do so in the face of opposition.

The market economy is indispensable for China’s development. Xi is not unaware of this, but the times of Deng, with their “being rich is glorious” slogan, have passed, and the Chinese president is of the conviction that economic development cannot question the established order. Therefore, he adopts the centralization of power, in the purest Leninist style, and a centralized power admits no rivals. The big businessmen, even if they´re members of the Party, have built up wealth that can turn them into suspects, an obstacle to “common prosperity,” which Xi refers to with a great deal of frequency. This would explain the campaigns launched in recent years against some of them, in the name of the fight against corruption, and which have affected, among others, Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba and accused of a dominant position in the market, or Xiao Jianhua, a millionaire fund investment specialist who was sentenced to 13 years in prison.

One of the conclusions of the Congress is that security – including digital, food and energy security – may be more important than the economy

As for the rest of China, its economic situation has worsened with the proliferation of restrictions derived from the covid zero policies, with the extensive and prolonged confinements. Consequently, the outlook for economic growth for 2022, which was 5.5%, has been reduced to 3.2%. No less disturbing are the increase in Chinese debt to 250% of the GDP and the decline in foreign investment in the country. Regardless of the effects of the pandemic or the consequences of the prolonged crisis in the real estate sector, everything seems to indicate that recovery will be slow because the regime will continue betting, in the name of “common prosperity”, on measures that could leave technocrats cornered by ideologues, since power always tends to value loyalty more than efficiency.

On the right side of history

In Xi Jinping’s address before the Congress, China was once again presented as an example for the whole world, as it boasts itself to be the only country capable of breaking up the West´s monopoly of modernization and its ideological conditioning based on liberal democracy. Instead, China would embody an independent model of development based on peaceful coexistence, friendship and cooperation, which does not seek to impose models on anyone. Quite a contrast with a West that continues to bet, in a variety of ways, on what it did in recent history: wage war and colonize.

Therefore, in Xi’s words, China stands on “the right side of history.” It is a message that doesn’t hide the country´s ambitions of being a world power, and adds yet again the touch of Marxist and Maoist determinism: “The wheels of history are rolling on toward China’s reunification and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” The reference to Taiwan is obvious, and while Xi advocates peaceful reunification, he refuses to promise that he will not renounce the use of force. It´s the same approach applied to the former colonies of Hong Kong and Macao. On the one hand, the validity of the “one country, two systems” principle, which facilitated the return to China of territorial sovereignty, stands, but politically there is no room for leeway. All these territories must be governed by “patriots”, that is, people loyal to the Party, which legitimizes Beijing’s interference in their political administrations.

One of the conclusions that can be derived from the CCP Congress is that security, which includes cyber, food or energy security, may be more important than the economy. This explains the drastic measures of the zero covid policy and the almost five million officials purged in recent years. The “Chinese dream” continues, and this implies promoting an exceptionalism, which is not so different from the American one.